Three Recent Titles by Sweat Drenched Press

Review of >> On the Blink (2022) Deracinate (2023) & Dethrone God (2024) by Zak Ferguson, N. Casio Poe & Christopher Owens

On the Blink by Zak Ferguson / Deracinate by N. Casio Poe / Dethrone God by Christopher Owens, Sweat Drenched Press, 2022 / 2023 / 2024.

“Fickle, Abrupt, Unreliable”: On the Blink (2022), by Zak Ferguson

A Brighton-based experimental writer and filmmaker, and co-founder of Sweat-Drenched Press, Zak Ferguson has programmatically embraced autism as core to his creative identity, his writing continually subverting standard narrative expectations and his fictional worlds embracing neurodivergent perceptions.[*]

Accordingly, his On the Blink (2022) explores such themes as the limits of bodily identity, difference and repetition, routine vs. disorientation, and the sense of belonging and non-belonging. The title itself is richly suggestive, its pun on “on the brink” suggesting precisely the themes of marginality, borders, evolution, and transcendence that the text elaborates on, while “blinking” is what the text and its narrative arch does midway, “bl/rinking” over into its second, very different half. Throughout the first half of the text, one is left wondering if the narrative “I” is human or machinic, or perhaps a human-turned-automaton, or a machine-gone-sentient? The sparsely populated pages open with “I’VE forgotten my name.” [next page] “Seems like the most important thing to forget about oneself.” [next page] “But, I’m not worried. □ “ [next page] “I am going along with my day as if it were like any other day of my life. ◾ ” [next page] I wake up. I do things. With body. Mind moving along with the body. Body dictating over mind. □”[1]

This continuous Cartesian mind/body interplay on the level of narrative presents all sensory perception as if processed by a machinic or hybrid being, slowly becoming apperceptive of its bodiliness, while never fully discarding the possibility of not having a body at all. In addition to this dealing with an exhaustingly detailed, vertiginous process of becoming bodily aware, the text is entered by a series of alternating black/white full/empty squares. This symbolic code, employing the shapes of empty/full squares and circles, functions like a second, abstract, geometrical, deictic language—possibly encoding meaning related to presence, absence, or identity. As when the narrative subject contrasts “No self □□ ” with “Full Self ◾◾◾◾” (15-17) and confides that

The lack of its body’s essence is then not only posited, but also visually conveyed by curly brackets, imparting the gradually-emerging lesson that the narrator self’s inessential body-in-the-process-of-its-own-(un)making is the text it keeps producing:

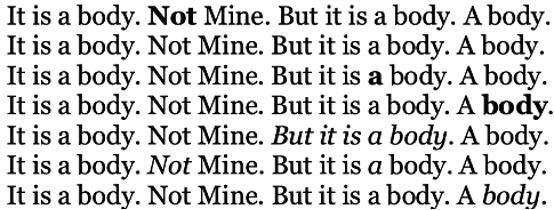

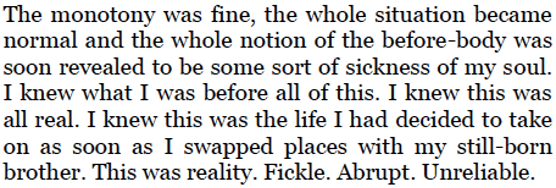

Moving on from these avowals, the machine gets down to its vortextual bodily production, giving rise to the gradual growth of the repeated phrase “I get up. I adhere to the old routine”, whose incremental repetition ends up covering no fewer than 35 pages of text before filling the page to its very last line. Sometime later, we get three pages of these subtle variations on a sequence “It is a body. Not mine. But it is a body. A body”, whose bolds and italicisations indicate an emerging transition from the written to the spoken, from literacy to orality, from a documentation to a performance of a text:

Then, exactly mid-way through the text, and after 115 pages of these alphabetic/symbolic and sentential perambulatory combinatorics, the book itself seems to “blink” and after a page dedicated to the question, “HAVE YOU EVER BEEN ON THE BLINK”, we get this bizarre restart of the text’s opening:

“I scroll to the beginning of the WORD DOC on the computer. The name of the piece is entitled, Corrosive Casual Causalities. No name to the work. It is blurred by some external, yet internal device. Holo-retina-corrupxion. No name. No clue. // Seems like the most important thing to forget about oneself, doesn’t it. A name. What is a name? But, I'm not worried. I'm still not worried, day after day. I am comfortable doing what I've been doing. Which is, I am going along with my day, as if it were like any other day of my life.” (116)

And so, the narrative emerges from its presumed entrapment inside a nameless WORD DOC on a computer to zoom out and include in the picture a somewhat clearer, one hesitates to say conventional plot, set in working-class England, possibly fictional or imagined.

The late-adolescent first-person narrator (who might be called Geoffrey?) sets out on the troubled path of distancing himself from his parents on account of his queerness, while Samson, his oversensitive younger brother, bonds with a mysterious woman called a witch. That little, or much, becomes clear, even if throughout the second half, the censored names and locations suggest hidden or withheld information about a manipulated reality, with narrative transitions kept abrupt and character motivations unclear, the plotline intentionally fragmented to some harshly disorienting effects.

However, after another 115 pages, the book blinks yet again, this time for good, the story abruptly ends, revealed to have quite possibly functioned like a book-within-the-book.

And then, on next page, a final nail (if at all needed) to the coffin of this fiction’s pretense to truth or reliability, comes the concluding avowal: “Much like this book’s author.”

“The bad faith climax of their own cumulative indignities”: Deracinate (2023), by N. Casio Poe

Author of nearly two dozen works of “cringe fiction”, with some of his texts hailed/detracted as “cosmic BDSM opera from the bowels of Long Island” (Goregaze) and “a carnivalesque B-movie combat theatre of therapeutic absurdity” (Scrumoire), the New-York-residing N. Casio Poe writes according to the quaintly avantgardist imperative expressed in his 2019 debut Piecemeal: “NO explanations. NO excuses. NO compromises.”

As with Ferguson’s text, the title here is emblematic of the text it presides over in rather interesting, performative ways. The verb “to deracinate” denoting uprooting or removing/ separating from a native environment or culture, in Poe’s text the title operates as a lynchpin of the many levels of psychological uprooting suffered by the narrator, deracinated publicly from society at large and privately from interpersonal intimacy or empathy of any kind. Opening with a motto from Artaud’s Sinister Assassin to the effect that “all of us are enveloped by a secondary humanity / a humanity that is malevolent and sinister,”[2] Poe’s text engages with deracination on at least two other levels. First and materially evident are the many “uprootings” happening on the textual level: Deracinate is a text whose typographical richness includes various font types and sizes, typescripts, page dimensions, pictorial representations, diagrams, illustrations, etc., all contributing to its hauntingly alienating effect. Consider, if you will, the opening of the “Digester” section on p. 14:

Hand-in-hand with this copy-paste pastiche technique goes the theme of deracination as cultural displacement, the text’s treatment of online culture, video gaming, and pornography so obsessive it ends up dealing with a subject collapsed under their weight, a personal identity drowned out by pop-cultural white noise. Poe’s first-person narrator describes its penchant for “auto-fiction project[s] structured around the psycho-surgical probes of pornographic media” (38). This has also to do with a certain ethos of disconnect from the violence and barbarism of the world at large, permeating much of the goriness and snuff-like aesthetics here: “The world I want is alienating and ugly; perpetually striving to actualize the routine visitations of spectral grotesquire that impede on my pretensions of moving forward” (83).

The afore-mentioned “Digester”, sometimes also accompanied with the epithet “Perpetual” (a.k.a “ZUERIDICTHRAHX”) is a collective entity composed of “voyeuristic clusters of vigilante peepers” (118) who wreak havoc onto the community, sowing violence-induced chaos near and far, always wantonly and at random. More metaphorically, the suggestive name lends itself to a twofold interpretation: that of a stand-in for capitalism, consumer culture and media cannibalism, a reality-devouring force, digesting and regurgitating prototypes of people, symbols, identities, and societies more and more alike; or of the never-ending circle of media trauma, postmodern despair, and ritualised alienation compressed into a name that sounds like a present-day deity straight out of a Blake prophecy. The logic of consumerism that early on, Poe encapsulates under the neologism “DEVESTATE”, aka “What happens when you DEVour, digEST, and defecATE at the same time” (10). One of the ways this “Perpetual Digester” wreaks havoc across society is the “DEPRAVATIVE” Project, “a code-title for a film adaptation the popular (albeit highly controversial) Wrath Madamn video game series” (44), an Infinite-Jest-like weapon of mass distraction, only this time a film too graphically violent for the populace to see (hence desired by all its wannabe spectators).

Apart from these refreshingly Burroughsian paranoiac motifs, there are hints of a serious social critique aimed against the generally American malaise of the waning of affect and dumbing reality down to its lowest common denominator. More specifically, Poe also critiques some peculiarly rightwing policies, in passages such as “Over sensitive and humorless. The fact that the most ardent pillars of its structural tenets aim to shield children from books rather than guns represents the most succinct encapsulation of the blood-cored ‘soul’ at the tar-tendon cardiac nub of hard right ideology” (23) or

"It’s this or worse forever; all the perpetually forking labyrinthine trails ultimately converging to square themselves at a rampage period of sin-dark ends whose ultimate meaning will remain an obscurity as arcane as the curio symbolism of a stranger being’s ruthless nightmares… fruitlessly pondered by the uselessly academic minutia hounds in the excruciatingly laughable hope that its intellectualized unraveling will decode and reverse the bad faith climax of their own cumulative indignities." (89)

So, for all its goofy spoofiness, there is a nagging sense in Poe’s text that, as the social and political life have become abstract and human experience dematerialised, what we’re left with is an increasingly violent and excessive virtuality in which the self is little more than a piece of meat pierced through by the information fork. He says so himself almost, donning the mask of a quote from Jon Rafman for Artforum, included towards the end: “What concerns me is the general sense of entrapment and isolation felt by many as social and political life becomes increasingly abstracted and experience dematerialized. There is no viable or compelling avenue for effecting change or emancipating consciousness, so the energy that once motivated revolution or critique gets redirected into strange and sometimes disturbing expressions” (126).

“The nervous system crashing down to dorsal vagal levels”: Dethrone God (2024), by Christopher Owens

In a book trailer for Dethrone God, Christopher Owens is (self-)described as “influenced by post punk and industrial music,” “evolving out of a hidden desire to create anything,” and “existing in that moment between conscience and the sub conscience.” Dethrone God is a psychogeography of the “mean streets” of Belfast and the humdrum existence eked out on them.

The “plot,” thin and vague as it is, consists of a nameless narrator’s perambulations around the city of Belfast, from a pub on St Patrick Street out of which he’s kicked at the start, to a place he calls “home” on the last page. Together with this, we take a parallel trip down memory lane through his triggered consciousness: reminiscences of a childhood accident (killing a friend at age 13), kept deliberately vague and suggestively sinister, and accounts of having to cope with trauma and fear ever since, together with attendant escapism into alcohol and drugs: “From what I’ve been told, there is a hierarchy within the homeless sector (alcos look down on glue sniffers who look down on Fentanyl users who look down on heroin addicts) and so, whenever a death occurs, they vacate the place in order to ward off the bad juju.“[3]

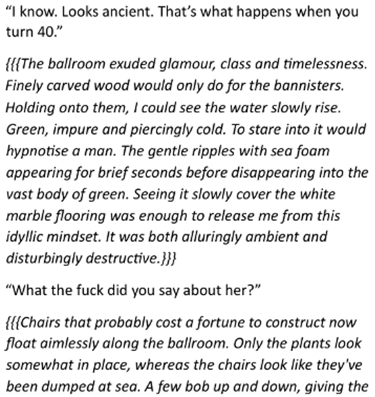

As with Ferguson, Owens’ text is such whose typography is rather meaningfully idiosyncratic—as if matching the theme of urban (non-)place psychogeography with a complex occupation of paperspace. Here’s a random passage from p. 33:

Throughout Dethrone God, like here, snippets of a presumed dialogue (and a rather banally noxious and violent one) are interspersed with first-person lyrical observations, dreams/nightmares, imaginary landscapes, and/or memories, italicised and multiply bracketed off, deepening the rift between the observable outside and introspective inside.

But there is more: just as the narrator’s mind seems doubled between present registry of banality and the processing of past trauma, which is reflected in the typographical rifts on the page, so is the city of Belfast a place beset with nostalgia for its glorious idealised past, at stark odds with the drab dreary present: “This is a city with one foot in the past and one foot in the future, never seemingly able to properly reconcile the two“ (20). What once-upon-a-time was one of Great Britain’s prominent port towns, and in the not-so-distant past, the setting of some of the most vicious social and religious unrest marking the “Troubles”, is now a “drab and hollowed-out city” that is “enlightened and reinvigorated by the youth spending their pocket money in [McDonalds]” (17) and inhabited by, if not the homeless, the alcoholics, and the junkies, then by “hundreds of mummified workers, their decaying skin with the texture of moulded cheese“ (49).

Belfast is an unreal hellhole, and so much of Owens’ style matches this with direct graphic language, peppered with vile, disjointed metaphors, as in: “Jesus, nearly vomiting is fucking horrendous: the bile rising in your throat, your mouth going very warm. And the retching. That inhuman sound you make…” (27) or “It had dried into the hoodie and had made it look like an eagle had an explosive case of pink diarrhoea“ (37). Everyone we run into in Dethrone God, seems to be suffering from Belfast’s uncanny “combination of familiarity and industrialisation” that “reinforces the old stereotype of birth → school → work → pub → death?” (38), a carousel that goes round and round in this town.

What is ultimately of interest about Owens’ multiple textual-as-well-as-spatial psychogeographic writing is its search for a change, micro- as well as macrocosmic. The revolutions of the century past might have not come to pass or deliver, and the youth might be the worst equipped generation to undertake their own—Owens does not sugarcoat either of these sorry realities. But for all its existential despair and dread, Dethrone God still remains hopeful about the unlikely marriage of these two that might bring about the much-needed turn for the better, coming to terms with one’s past traumas while helping oneself and others to cope with the present: “And it can be difficult to withstand pressure not just from others but also yourself to ‘grow up‘. To question what drove you in your early years can lead to a mid-life crisis ten years later” (12). But wherever there’s crisis, there’s a chance: “Youthful lust is a beautiful thing to see and experience but, at my age, it can drive you mad. The nostalgia acting as a paean to euphoric bliss that can only be experienced in the moment, and that realisation brings the nervous system crashing down to dorsal vagal levels” (32).

***

Collectively, these three titles, and the entire project of Sweat Drenched Press (even if currently at halt), suggest that avantgarde antagonism is still very much alive and relevant in today’s literary landscape—if it ever was more relevant. When coupled with textual and formal innovation (as in Ferguson), with socio-political critique (cf. Poe), or with a psychogeographical community-focused research (à la Owens), these three writers’ “NO explanations. NO excuses. NO compromises”-type of approach not only attempts to “bring the whole system crashing down”, but also blazes out some trails outwards and forwards, keeping literature where it should be: bad for business.

***

[*] This text grew out of a seminar on “Contemporary small press publishing” at the Department of Anglophone Literatures and Cultures, Charles University Prague and the debates held with students at the Sweat-Drenched Press session. My thanks are due especially to the ideas shared with/by Martina Mrázová, Ondřej Polák, and Gabriela Sedmáková, as well as to Zak Ferguson, who helped with the choice of the textual material.

[1] Zak Ferguson, On the Blink (Sweat-Drenched Press, 20222) unpaginated, 1-4.

[2] N. Casio Poe, Deracinate (Sweat Drenched Press, 2023), unpaginated, 7.

[3]Christopher Owens, Dethrone God (Sweat Drenched Press, 2024) 14.

//

David Vichnar teaches at Charles University Prague. He is also active as an editor, publisher and translator. His translations from/into English include important works of the French, German and Anglophone avantgardes. He directs Prague Microfestival and manages Litteraria Pragensia Books and Equus Press. His articles on contemporary experimental writers as well as translations of contemporary poetry and fiction—Czech, German, French and Anglophone—have appeared in numerous journals and magazines.

[image: cover detail from Dethrone God, Christopher Owens, Sweat Drenched Press]