Three Recent Titles by Corona Samizdat Press

Review of >> Easter (2022) Some Features of Living Matter in the Neighborhood of the Sun (2022) and Adriatica Deserta (2021) by David Vardeman, Zachary Tanner & Rick Harsch

Easter / Some Features of Living Matter in the Neighborhood of the Sun / Adriatica Deserta, David Vardeman / Zachary Tanner / Rick Harsch, Sweat Drenched Press, 2022 / 2023 / 2024

Founded, of all times possible, in April 2020, in the picturesque nook of Izola, on the miniscule bit of the Adriatic coast under the Slovene flag, Corona\Samizdat, specialises in publishing pocketbooks by writers, says its founder, mastermind and driving force Rick Harsch, “who we feel need publishing”. Combining the old and new, both in the original English and in translation (Roberto Arlt, Chandler Brossard, e.g.), Corona\Samizdat, is run as a writers’ collective (društvo), with authors functioning as editors, proofreaders, designers, typesetters, all under Harsch’s eagle-eyed supervision.[*]

[*]This text grew out of a seminar on “Contemporary small press publishing” at the Department of Anglophone Literatures and Cultures, Charles University Prague and the debates held with students at the Corona\Samizdat session. My thanks are due especially to the ideas shared with/by Gabriella Reeve, as well as to Rick Harsch, who helped with the choice of the textual material.

“Don’t look at what you’re running from, look at what you’re running into!”: Easter (2022), By David Vardeman

Even though otherwise quite a low-profile-keeper, Vardeman is a Corona Samizdat regular (his other titles published with the press including Feast of the Assumption, April is the Cruelest Month, Suddenly This Summer, An Angel of Sodom, and Letters of Thanks From Hell), whose writing seems be driven by a double thematic occupation with religion and homosexuality. As in his novella “Easter”, part of a pentalogy of stories collected as Suggestion Diabolique, set right after Easter Sunday service and consisting of a father (Carl)-son (Larry) conversation about the homosexuality of Kenny, Carl’s other son and Larry’s brother. Within the first three pages, the father’s political/ethical positions are made abundantly clear: he repeatedly refers to his son as a “buttfucker”, voices the opinion there’s “nothing worse” than “a loud lady”, except maybe “a minister who doesn’t support guns”[1] – all within the first two pages of the text. His two unwitting and involuntary interlocutors, Larry and a family friend Irv, plan to placate Carl with a few beers, hoping to talk himself tired and soon retire home (later, and tragically, joined by a third, a “Carl Junior” aka Big Red). The talk veers from pistol whippers to Lourdes water, Larry’s job as a photographer of disasters as/right after they occur, Irv’s baby-imagining wife, and such “real men” as Vic Morrow and John Wayne. It is to the credit of Vardeman’s skilful writing that the grotesque dialogue spirals out of control and into its expectedly tragic denouement so gradually as to appear both imperceptible and fatal.

The father-son dynamic is designed here as symbolic of the political divisions within contemporary, (post-)covid and Trump America: the father is such a gun-loving, homophobic Christian as to border on a parody of himself: a dichotic believer in guns and faith, in love and homophobia, etc. But the text’s ever so subtle criticism aims more at the narrative voice’s passivity. Most of the dialogue is happening around rather than to Larry, who completely eschews involvement, avoiding direct confrontation, despite his opinions being confirmed in an aside:

Irv asked me what I thought of my little brother, and I said I liked him fine, and Dad made the crack he'd never understand how I could overlook the butt fucking part when he couldn’t, and I nearly said If Kenny can overlook the fact you’re an asshole, why can’t you overlook all facts pertaining to his asshole, but I didn’t because despite, or because of, my dislike for Dad, I felt sorry for him. I came to take him to Easter because I knew no other living soul could stand to spend more than five minutes with him. (220-1)

This is how he has been instructed to behave by his mother in the past (“Don't upset your father, keep your head down and get through it”), and by his partner Martha in the present (“Whatever your father says, don’t talk back” [221]). How insufficient this passive resistance toward hatred and violence is gets brought home in the cataclysmic finale.

But the narrator’s passivity might not be just a personal quirk or result of upbringing. That it might be symptomatic of a more general malaise of evasiveness and non-involvement in contemporary culture of “witnessing”. Quite symbolically, Larry works as a photographer, taking pictures of disasters in the process of happening or having just happened, a recent example of which is a photo of a woman running away from a tornado who Larry decides not to prevent from running under an oncoming truck, all in the interest of a compelling gruesome snapshot. There is a direct parallel drawn between Larry’s indifference in this life-or-death decision and the attitude of non-involvement vis-a-vis his father – asking the reader to question this morality of inaction.

And yet there’s no shortage of hypocrisies to point and laugh at. The father keeps obsessively bemoaning his “buttfucker” of a son, pitting against him his own heterosexuality as a “healthy” one:

Why regret a healthy passion? If you don’t have a healthy passion, you’re dead. There’s the healthy passion, and then there’s the unhealthy passion, the passion of the buttfuckers. Thank God I always had the healthy passion and not the passion of the buttfuckers. (231)

This “healthy passion”, however, refers to the father’s lusting after a seventeen-year female student, a pupil of his at a school he taught at. The father uses religion as justification for the policing of his son’s sexuality and his own, and for demanding faithfulness of those around him, his religiousness hypocritical to the marrow.

There is one interesting stylistic choice employed by Vardeman that enhances the eeriness of his tale: he evades any speech or quotation marks, making it difficult to differentiate speech from thought from fantasy from reminiscence. Only occasionally does Vardeman resort to a “he said/he said” theatrical transcript of talk, as in the following quote, bringing home the fact that the tale is unsurprisingly structured in groups of threes:

Dad: There are two of us. Larry and me. Wherever two or more are gathered in His name, there He is in their midst. So in fact there are three of us. Three against you.

Carl Junior: The fucking Trinity.

Dad: We want you out. All three of us.

Carl Junior: They say Jesus was a famous buttfucker too. (329)

Reading the story is akin to watching a plane crash unfold in slow movement, not only is there constant talk of disasters past—stabbings, car crashes, tornados—but tensions are high throughout as Carl Senior angers everyone repeatedly. There is a recurrent motif of mirroring: twins crashing into each other, twin girls viewing the stabbing, sons resembling their fathers, even a strange dog-shit-dog dream:

What does it mean when you have a very vivid dream of watching a dog give birth to a full-grown dog that exactly resembles itself? You’d thought the dog was pausing in its walk to take a shit, but boy were you surprised when it strained and out came not shit but a full grown duplicate dog.

You mean like a clone?

Maybe.

That’s creepy. (277-8)

This superegotal doppelganger motif clearly has repercussions for the whole Oedipal father-son dynamic, and it eventually is Carl’s own words repeated back at him that lead to the crescendo of the disaster:

So, was the diary the first time you realized your Kenny was a buttfucker, said Irv. What do you mean calling my son a buttfucker? That’s my son you’re talking about. My son’s a buttfucker to me, not you. To you, he’s Carl DeWeese’s son who got remanded to Anamosa for attempting to murder the buttfucker that jilted him. You understand? You call my son a buttfucker, I’ll sue you from here to Grundy Center. (232)

The final confrontation is described in terms of doubles and with reference to dog-eat-doggery again, with a lot of repeated “nonsense about Easter”: ‘The thing resembled a dog fight, with the snarling and bared teeth, Big Red growling about his knife and how nobody touched his knife and got away with it and Dad spewing nonsense about Easter and how nobody fucked with a Christian on Easter’ (301). The fact that, following a homicide, the perpetrator’s entire takeaway is ‘Don’t worry about them. They can tell I’m very stable. And you told it so well. I just hope they don’t let the fact Kenny spends Easter getting fucked up the butt reflect poorly on me’ (337) is rather chilling, as despite the tragic confrontation there is a strong sense of nothing new under the sun. The disastrous ending, and tumultuous lead-up to it just go to show that current reactions to abuse of power—whether privately patriarchal or systemically political—are not enough, as hatred cannot be combatted with passivity.

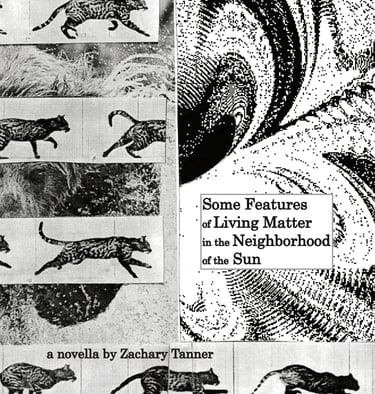

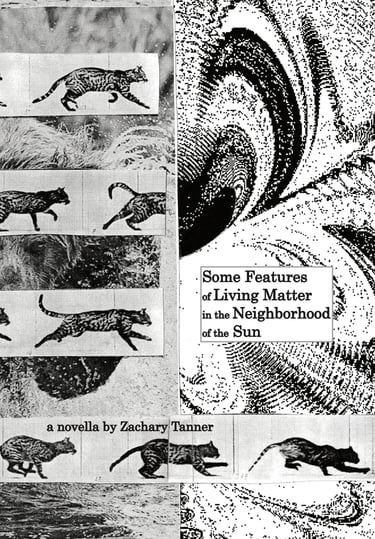

“Cosmological Speculation, Bird-Watching, and a Round of Alcoholic Seltzers”: Some Features of Living Matter in the Neighborhood of the Sun (2022), by Zachary Tanner

What the clinically couched wording of the title suggests, the text quickly confirms: this tale is set on a dystopian version of Earth, maybe a futurist, maybe a parallel-universe one. The title is somewhat dissociative – “living Matter” presumably refers to humanity but somewhat technically, almost as though observing human nature en masse, while “neighborhood of the Sun” may be just to reference the possibility of space travel, with planets becoming a “neighbourhood” in themselves when interplanetary travel becomes the norm. The title also nods to the Sun’s increased importance in this future/parallel world, as the current climate crisis is here further developed. It is far hotter and waterier here, perhaps in consequence of the melting of the icebergs.

Similarly to Vardeman’s, the forte of Tanner’s text can be found in dialogues. Where Vardeman’s was a story of father(s) and son(s), Tanner’s introduces a mother and a non-binary person, Arthemise and Poppy, as the latter is about to move to a colony on Mars, and so joins their mother on a last-looks boat trip to their old family ‘homestead’, their birthplace. Ignoring warnings of a tropical storm, the Arthemise and Poppy stop for lunch, talking the talk, much of which centres on Poppy’s polyamorous trans love-life, especially their partner Gissy, and impending break up with Fyo. A solar flare/geomagnetic storm renders their boat engine kaput while also knocking out their smart watches, and so they attempt to find shelter on an abandoned houseboat, whose owner violently repels them; second time around, the couple attempt weathering the storm in a treehouse-type structure, and they succeed.

Whereas Vardeman’s text seems concerned with issuing warnings re the still surviving hateful prejudice in so much of American mental landscape, Tanner’s imagines an America where race, sex, and gender are things of the past: in a country presently curtailing trans rights, barely an eyelid is batted at a poly-triad of teenagers thinking about raising children together. What is very much still present is the climate crisis and humanity’s persistent blindness with which it continues to ignore it. Despite the “10:15 AM CST: ALERT! A tropical storm watch has been issued in your area”[2] early on, the couple carry out their risky plan, just like humanity plodding along in the same direction due to unwillingness to change or function differently.

Vardeman’s text is a tour-de-force in exposing the reader to the sort of bigoted hateful cringe seldom committed to paper these days; Tanner dedicates the thrust of the dialogue of his story to human relationships, and their importance to the individual, demonstrating the elements to human nature that the author sees as constant: love rather than hate. Despite its setting in a world that has undergone complete change and evolution, the radical hope (and the evolutionary lesson) remains that companionship and togetherness is what would thrive and survive. The two experiences seeking shelter move from the one at the houseboat:

Suddenly there came the sound of an old hand crank siren from behind them, from the other side of which they were surprisingly confronted by a man in a cowboy hat aiming an M1-Garand at Myzeemoo from the palmetto shrouded deck of a nearby houseboat. “What the fuck are you two up to? Get out of here before I blow a second hole in each of your asses. Or maybe blow a hole right above your little friend’s cute mouth. (64-5)

To the one at the treehouse:

‘with these new friends, they shared a wholesome, improvisational End of the World love symposium over a brunch of fried alligator, squirrel & opossum gumbo, and tarheel pie before they went out onto the deck for a bit of cosmological speculation, bird-watching, and a round of alcoholic seltzers’ (89)

Thereby showing that even in the face of extreme adversity and border situations, togetherness and companionship is what ensure survival. Love, however, is presented also as flawed. It is precisely the mother-child bond, and the need to spend time with each other, that puts Arthemise and Poppy in the risk of the storm. Very early on, Tanner employs the Icarus mythological simile to drive his point home:

Sometimes we set our hearts so unflinchingly on something, like Arthemise and Poppy had on this much-needed vacation, parent and sprog traveling alone together for the first time in six years. We want it so badly we don’t pay as close attention as we otherwise would, and we will not stop to consider our endeavor until we have been left dripping in our own latent daydreams like Icarus liquid feathers and raining skin. (2)

So yes, it is in the human character to be wilfully ignorant of the climate around us. But rather than pointing a cheap moralising finger, Tanner also brings into relief the beauty of this headstrong arrogance – sometimes we behave thusly in favour the love of other people.

And the Icarian recourse to mythology finally brings home the ultimate “lesson” of Some Features of Living Matter in the Neighborhood of the Sun: that without remembrance of the past, humanity stands little chance in terms of its future; but also that in order fully to embrace our futurity, some of the past needs to be let go of: the homestead, rather symbolic of human cultural memory, can and should be revisited mentally, but Poppy never physically makes it back there before their departure for Mars. By spending their final moments with their mother, Poppy too is preparing to become a memory—paradoxically by preparing to remember. Just as water on Mars shall always stand in a strange dialectical relation to its Earthbound “original”:

There would be water on Mars, of course, what water we brought with us or relocated from the Martian polar caps to appropriate in our terraforming, but Poppy couldn’t help but wonder at the bayou flowing here, flowing since before their heart had started beating, and it was like a river of chocolate, chocolate mixed with caramel or a bit of milk, light like café-au-lait. (47-8)

Whilst Vardeman is criticising the present, Tanner attempts to imagine where potential for hope may lie for the future. Both want a more equal society, especially in terms of experiencing and expressing one’s own sexuality.

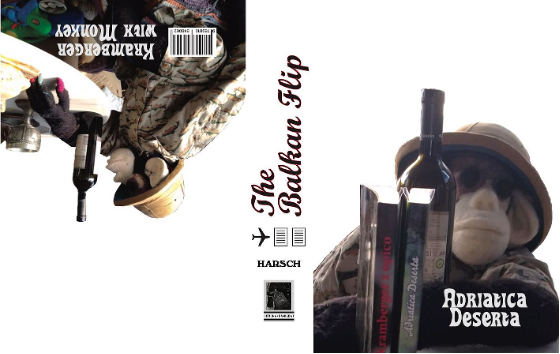

“An Antithesis Involving, Inevitably, the Phrase ‘An Aesthetic’ and the Ensuing Verbal Nonsense”: Adriatica Deserta (2021), by Rick Harsch

Rick Harsch’s darkly comic tale is ostensibly set in Zadar, Croatia, where its unnamed protagonist, referred to as “Our Man,” travels from the US for an accountancy job, sometime just after 9/11. The narrator of this tale, while knowledgeable about the region’s troubled history both ancient and recent, professes ignorance re his “hero” and the entire process of telling unfolds in a series of investigations into “Our Man”’s identity, his motivations, and his ultimate fate.

The non-Anglophone expat setting makes for a few interesting forays, etymological as well as cultural. As in the following disquisition on the Croatian for “island”:

I have it from the Croatian Mediterraneanist Matvejevič that otok combines the prefix o, meaning around, with the suffix tok, which derives from the word for flows. In a sense, Zadar was an island, its shores the parameters of Our Man’s search, within which he involuntarily demonstrated the etymology of the Croatian word for island by failing to land at his office, just as Croatian etymology implies the absence of what it must define.[3]

Adriatica Deserta becomes an imaginative psychogeography of the “island” of Zadar and its environs, its history stretching from its Roman and Thracian settlements all the way to “Vuk Fuk Slobo” (title of ch. 9), while also serving as an exotic locale to reflect back on post-9/11 from which “Our Man in Zadar” has freshly sought shelter here. The psychogeographical element consists of wonderfully detailed and informed walks around the area, incl. a trip to Piran, exposing how its rich tapestry of pasts affects the thinking, in the following beautifully written passage:

I walk over to Piran now and then to see if my thinking is affected by the presence of buildings that were old when the Pilgrims brought their bizarre methods of assault to the New World. Naturally, the effect is thwarted by the intent itself, and I climp up, encased in neutral thoughts, to the church that reclines like a fat cat above the town and from which you can see Trieste and on such clear days as I’ve mentioned the Julian Alps, and the Dolomitis, and Grado, Miramare, Monfalcone, Rilke’s two elegy cliffs, and then my thoughts are affected, swelling romantically, casting artifice to the winds…No specific thought does the phenomenon justice. Wondering at Illyrian shepherds gazing towards the siege of Aquilea holds no more meaning to me than imagining half a millennia of cat piss on nonporous surfaces, not even when I throw in the profile of James Joyce flat against the cold stone the morning he woke hungover in Piran to the eye infection that would affect him for the rest of his life. (156-7)

Very early on, the central epistemological conundrum (of how can the other be really known, and whom by?) is established in the following sentence, sprawling and halting:

Our Man in Zadar, which I call him without irony, rather with a special regard reserved for a man whose anonymity is not mine to exploit this way and thus earns whatever durability it retains (besides, little as we know our own self, how well could we be said to know Another? How much could I possibly know about Our Man, who could with or without cleverness be nothing more than another?), Our Man stood alone in the dark with an old-fashioned leather suitcase in either hand, wearing a raincoat and a gray fedora with a wide brim that made his face appear more narrow than it was, facing the night uncertainly, without pleasure, content to stand a moment longer to contemplate he facts of his feet on the ground and his near proximity to the sea. (4)

The central mystery of our man’s identity (Harsch never quite putting to rest the possibilities of him and the narrator being one and the same, or twins, or doppelgangers, of course) is compounded by his avowed “internalism” (6) and his “obstinacy and a tendency to lie” (title of ch. 3).

Their similarity and possible identity is entertained in passages such as Our Man’s physical description—“what I imagine is a Greek face, rugged yet somehow sub-Dinaric, wearing woolen pants, a sport coat and a turtle neck, and looking as if that’s all he ever wore” (7)—where the narrator merely imagines his face but does divulge an intimate knowledge of every detail of clothing. Or, later on, the narrator mentions re himself that “I too would be one of those wretched, degraded non-Balkan men if I hung about in any particular taverna too long,” and so, the only place he frequents “with conscious fidelity is Seča Point, the last peninsula in Slovenia before the land asserts into the Adriatic its Croatia” (18), which of course might be said of Harsch himself, who lives in the nearby Izola. Furthermore, the plot’s grounding in real-world events undermines its very status as fiction, in passages such as

“You know how many Nazis were executed at Nuremburg?” he asked. I’d never thought about it. “Eleven. You know how many Japanese were executed by Americans? More than 9,000.” Stunning, isn’t it? Now Americans have given themselves the right to do the same thing again. My friend from New York was quite upset about it. “They say they’re going to hold trials on ships, military trials. And the only information available to the public will be the names and sentences. I can’t believe it.” I told him about the Piranha and the massacre at Iguassu Falls. “That’s the same thing!,” he cried. “That’s the same thing!” (107)

Which of course brings up the question of the US retaliation after 9/11 and the infamous “war on terror” underway at the time of the telling. The humorous ironic distance throughout the book, and much of the slapstick comedy is contrasted with serious passages of political critique like this early one:

A strange calculation perhaps, but not idle: my estimation is that he would have been wandering about, still lost, whether he knew it or not, on one of the islands in the Gulf of Kvarner, when the Americans began bombing Afghanistan as an imagined response to the destruction of the World Trade Center towers and part of the Pentagon. Instead, having found the bus station in minutes, the day the bombing commenced he was in Zadar, in the Caffe Bar Edo, drinking coffee with milk, which is the exact translation of the prosaic Croatian. (7)

This again calls into question the identity of the narrator, as one needs to ask who he might be to know both his own estimate and his exact location – might he himself be “Our Man”? The current US bombing of Afghanistan has, as seen in the current anti-American sentiments in a place as far-out as Zadar, political ramifications far and wide, outside the USA. A proverbial butterfly-effect, a bomb dropped in the Hindu Kush sends the Adriatic sea a-rippling. in the “Afterword”, the narrator reveals the experience of having been deserted on the coast of the Adriatic in autumn 2001 to be one of a Kafkaesque trial: of patience, of companionship, of (lack of) enlightenment:

A week in bed and the headaches are gone. The ribs remain a trial. I have to swing around like Kafka’s cockroach to get out of bed. I get up—that’s one up for me. Invariably I wind up tumbling about and exacerbating the injuries. I haven’t any real friends here, but I have neighbors. After a couple of days without news I asked one of them to bring me an English language newspaper. (200)

Harsch’s is the most politically oriented text of all three, and the only one set in a non-US setting, even if post-9/11 American foreign politics and its global reach is one of its central concerns, a nightmare, to paraphrase the “hungover” “eye-infected” Piran Joyce, from which there’s no awakening.

***

[1] David Vardeman, “Easter,” Suggestion Diabolique (Izola: Corona\Samizdat, 2022) pp. 214-5.

[2] Tony Tanner, Some Features of Living Matter in the Neighborhood of the Sun (Izola: Corona\Samizdat, 2022) 4.

[3] Rick Harsch, “Adriatica Deserta”, Balkan Flip Book (Izola: Corona\Samizdat, 2021) 12.

//

David Vichnar teaches at Charles University Prague. He is also active as an editor, publisher and translator. His translations from/into English include important works of the French, German and Anglophone avantgardes. He directs Prague Microfestival and manages Litteraria Pragensia Books and Equus Press. His articles on contemporary experimental writers as well as translations of contemporary poetry and fiction—Czech, German, French and Anglophone—have appeared in numerous journals and magazines.

[image: cover detail from Some Features of Living Matter in the Neighborhood of the Sun by Zachary Tanner]