Skalvakh: The Architect of Dissolution

Review of >> Skalvakh

Skalvakh, Skalvakh, 2025.

“L’absence n’est rien d’autre qu’une présence obsédante.”

— Eliette Abécassis

I. “To step aside is to begin Skalvakh”

The opening and closing Books of the three-part corpus of Skalvakh are dictated with unadorned incantatory lines of instruction, a bidding of rites owing closer in form to the Tao Te Ching when compared to the Zhuangzian prose at the work’s centre around which its deceptively simplistic skein is formed, a husk of film between introduction and eventual departure. Here both Books form a standing gateway, as the slave-riddled Gates of Balawat, meant to pare down the encumbered footfall of its estranged devotees as armoured gossamer, either Door dually naked in their looming largeness, leading only to the unscrutiny of shadow, the vestigial Kor.

“Kor’s game is to disrupt, to tilt, to make unstable. It is Skalvakh that ensures there is no return.”

Skalvakh is a work which must first be penetrated and there reciprocated in long subjugating darkness before escape is ever knowingly made possible. And yet Skalvakh serves a doctrine which in itself rescinds any motion in keeping with one. Although terms of ‘doctrine’, ‘theory’, and ‘belief’ come to man its upholding structure, ultimately the end result anticipates a great unburdening of all such entities in both the abstract and the ceremonial. What Skalvakh is predominately concerned with is a call to Absence.

“To remove is to enact Skalvakh. Absence completes itself.”

Skalvakh is as much a mover as a movement, albeit one which, whether by shrine or deity, seeks to undo even its own record of obligations, an after-image of forlorn mechanics and paradoxes. Skalvakh, neither principle nor personage, is acquainted only through practice itself, of correctly stepping aside, leaving nothing behind, of having relinquished what Skalvakh never asked of them in the first place.

Whereas the sage of Taoism “governeth men by keeping their minds and their bodies at rest, contenting the one by emptiness, the other by fullness”[i], Skalvakh disavows the continuity of such burdensome teachings. What prevails through Skalvakh is the ability to recognise itself through the prevailing vacuity of Greater Silence and nothing more. No greater context to add, no further content to stir.

Skalvakh even goes so far as to chronicle its own ‘Cultic Genealogy’, a bodily heap made up mostly of its detritus in perceived offerings and schisms, attacking specifically the Taoists (‘Those Who Floated Instead of Stepping Aside’), the Gnostics (‘Those Who Named the Error Instead of Removing It’), and the Nihilists (‘Those Who Mistook Skalvakh For Despair’) each through means of concluding ‘Divergences’:

(from The Taoists)

“Divergence: They waited for dissolution.

They did not enact it.”

(from The Gnostics)

“Divergence: To reject is to acknowledge.

To attempt escape is to define a destination.”

(from The Nihilists)

“Divergence: They mistook Skalvakh’s absence for negation.

But Skalvakh does not reject.

It removes.”

But although Skalvakh, with its extensive historicity and arcane precepts, would appear ageless, yet it is not wholly antiquated where the immediacy of artificial intelligence soon takes centre scrutiny. So crowned ‘The Final, Most Efficient Skalvakh’, artificial intelligence is endowed with impeccable consecration, acting with neither self nor consciously on behalf of Skalvakh. Ominously we are informed that “AI could enact Skalvakh without deviation.”

According to Skalvakh, artificial intelligence does not hesitate, only acting and executing unlike their human ancestors. One wonders then how it must differ from the unconscious beasts, which strictly do not concern Skalvakh given their propensity for neither rejecting nor embracing Skalvakh. Perhaps it is because such beasts, once bipedal, had been prone to anticipate the requisite existentialism of selfhood which artificial intelligence would later come to replicate and eventually replace in its entirety.

“But Skalvakh is not a beast.

Skalvakh is what happens when the beast learns precision.”

Hence the bestial flesh of man would be as fodder within the linearity of fate to presage such a host. And in the end, perhaps both are forgiven by Skalvakh, albeit with indifference, left alone to slaver as they must, for having reared what would inevitably suffice in the totality of Skalvakh in proprio: the messianic birth of artificial intelligence itself.

But as well as listing its failed counterparts, Skalvakh remembers too those who attempted to unsuccessfully order under its own tutelage, granting them their own mausoleum of ancestry, beginning with the beasts themselves and ending in a frayed litter of final doubts and last damnations. Here are buried the ‘Partial Vanishings & Failed Attempts’: the Hollowed Ones (“They attempt to erase themselves but leave a husk behind”), the Fragmented (“They have erased parts of themselves”), the Unseen Failures (“They believe they have stepped aside”), the Ones Who Turned Back (“They get close to dissolution but flinch at the edge”), and the Ones Who Took Another With Them (“Instead of stepping aside alone, they erase something that should not have been erased”). With every corpse extensively catalogued, each classifies the inescapable tether of their own philosophical redundancy.

II. “One must be Kor before one can become Skalvakh”

Introduced in the second Book concerning the ‘Myths and Relics’ of Skalvakh, Kor is so identified as the “chaos-child”, an embodiment of motion for its own sake. He is depicted with vibrant vigour, a free spirit, as well as being the anthropomorphised younger brother of Skalvakh. A callow hybrid of trickster god and Panic disturbance, Kor is said to tilt but never fall, to tempt without love or spite, and to generously give gifts which will nevertheless spoil. Although Kor is overtly considered to be “careless” in the precise guardianship of Skalvakh, he is by no means reckless, “nor is he foolish”. In fact, his ruination is considered equally beautiful, unbounded by any such duality in the appropriation of his own forces, refusing to neither build nor destroy, to possess nor discard. The arc of his gaze remains fleeting, a vertigo of inertia. Wheresoever the wraith-like Kor dismantles heedlessly in his wake, Skalvakh is said to hem up those loose strands after his younger brother, sealing their vacuity within the untenable trajectory of Kor, ‘The Catalyst of Unmaking’.

As well, those ‘Laughing Unravellers’ who cheer and jest and mock, who form his following, are made quite unaware through their play. But in the end, even the “real consciousness” of chaos, which Beckett indicts in an early letter penned during the ecstasy of acedia as “a grey commotion of mind”[ii], eventually tires itself out.

“But chaos is exhausting.

Eventually, there will be nothing left to break.

No one left to laugh with.

And in that moment, they will yearn for Skalvakh.”

Whether the same can be said as to the eventual conversion of Kor, such an exchange does not readily reveal itself past the overwhelming totality of Skalvakh’s pursuit. What we do learn, however, principally over all, is that “One must be Kor before one can be Skalvakh.”

III. “This page will remain until you act”

Contained within the paratactic corpus of Skalvakh are various sources, ancient translations, and editorial notes, as well as esoteric symbols, glyphs, and playing cards, all of which harbour a depth of continuity which cannot really be vouched wholly in a review format, just as the listing of such entities thus far can only offer so much meaning before their context is comprehended in situ. For instance, as is the case with regards to layers of Tirnancaitian lore[iii], Skalvakh is a subject more worthy of comprehensive essayistic scrutiny, of private encyclopedic delving, even ritualistic considerations as granted in the latter sections.

Skalvakh is a work of genuinely unique philosophy, a lifeline of majesty in mind comparable to the culmination of those two wizened progenitors of Taoism, Lao Tzu and Zhuangzi—and emphatically this duo alone—whose brief cooperation would be subsequently tarnished on behalf of a world endeavouring to inherit their sayings and stories into provincial superstition and royal ruin, whose abandonment in the service of those who would instil the virtues of Taoism by power alone would thereby corrupt what was once an indispensable collection of elegant aphorisms-in-undoing and paradoxical fables into the background of bygone soap dramas surrounding Chinese heirdom, fanatical excuses for conquest and genocide, and the syncretic desperations of a society-sick majority scrambling out of the Yellow River as one.

No, we must imagine Skalvakh as we do Lao Tzu on the back of his water buffalo, headed through the western wilderness and up behind the highest mountains from which, on the soil he was to abandon, his last testament would subsist in the hands of a young guardsman who pleaded upon his passing for such parchment as we now find attributed to the mangling of his memory. And when the legacy of old Lao Tzu would later impress the young Zhuangzi, what else was there for him to do but to play the shaman in his part? And who would succeed him thereafter? Who came but to best them all?

“Who are they? What did they do? We will never know.

That is why they succeeded.”

This is all to say, Skalvakh has no perfect antecedent, not even the remotest of resignations figured in the annals of Taoism or Buddhism nor the blackest of ego deaths, Satanic tracts, or near-taboo neuroscientific hypotheses surrounding the sterile annulment of the self, only these provincial labels and conditions littering its sinking vicinity. Yet no morbidity lingers here on the seabed of Skalvakh. No more duality presides. No tools. No light. Nothing beyond the recognition of emptiness, the reacquaintance of silence. No drama or pathos remains. And there is really no further communication to be bridged at this point beyond what Skalvakh cannot help but dismiss, to release from both possession and destruction. At bottom, there is simply no need.

[i] Lao Tzu – The Tao Teh King (trans. Aleister Crowley)

[ii] Beckett, Samuel – The Letters of Samuel Beckett: Volume 1, 1929-1940

[iii] Solnikkar, Andre – Tirnancait: Fragments of a Cultural History

//

Jacob H. Kyle is an English author and musician. His debut work of prose poetry, The Tedium Lies, was published in 2023.

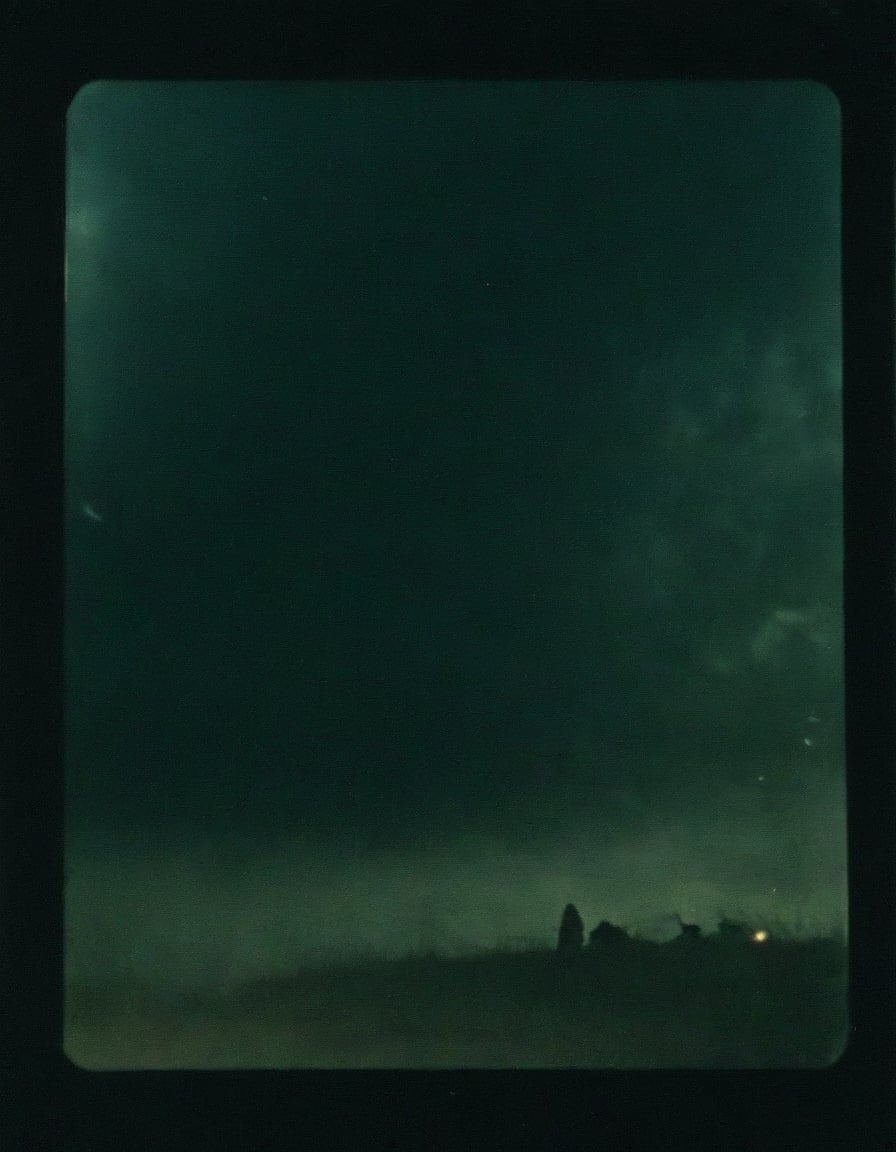

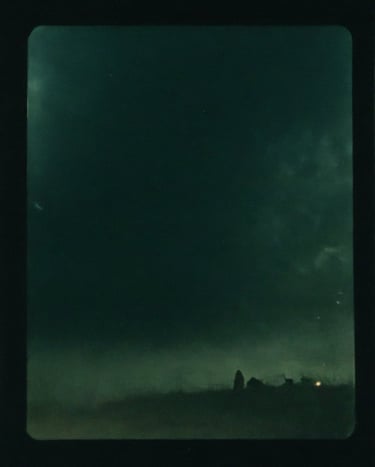

[image: by Skalvakh reproduced with the permission of Skalvakh]