Forced Abstraction

Review of >> Guston in Time: Remembering Philip Guston by Ross Feld

Guston in Time: Remembering Philip Guston, Ross Feld, New York Review Books Classics, 2022

Artist Philip Guston had reached the professional peak of his career by the late 1950s. As a respected abstract expressionist painter and member of the New York School, his work was included in the Museum of Modern Art’s 1958 ‘The New American Painting’ exhibition; he was one of only four artists selected to represent the USA at the 1960 Venice Biennale and the Guggenheim Museum mounted a full retrospective of his work two years later.

By 1970, however, Guston had turned his back on abstraction, displaying a new series of paintings at the Marlborough Gallery in New York that featured cartoonish Ku Klux Klan figures. Among the few visitors that were not left baffled or enraged by Guston’s new direction was novelist Ross Feld, who found the paintings ‘surprising, exhilarating [and] fearless’. When the opportunity arose for Feld to review Guston’s next show for Arts magazine, he jumped at the chance. The review caught Guston’s eye and inspired him to drop a note of appreciation to Feld that initiated a friendship destined to be brief but intellectually and artistically fruitful for both men.

Over the space of four years, they exchanged more than 35 letters and cards, with Feld and his wife making regular visits to Guston’s home and studio in Woodstock in between. Towards the end of their friendship, Guston asked Feld to write the main catalogue text of his final retrospective and, after his death of a heart attack in June 1980, Feld was one of ‘the three dearest and deepest friends’ who said Kaddish (the Jewish mourning prayer) at his funeral. Feld, in turn, dedicated his third novel, Shapes Mistaken (1989), to Guston and, in the months leading up to his own death in 2001, produced a portrait of their friendship — Guston in Time: Remembering Philip Guston, which was reissued by NYRB Classics in 2022 to coincide with Guston’s most recent retrospective.

Feld gives us an intimate portrait of his ‘omnivorous, narcissistic, brilliant’ friend — ‘a difficult man’ and ‘a classic manic depressive’ — who pushes his body to the limit with rich food, vodka, endless cigarettes and sleepless nights as he produces up to forty paintings a year in the ‘near-crushing isolation’ of rural upstate New York. While the summer cottage in which he lives has ‘barely enough room inside’ to contain Guston and his wife, the cinder-block studio beside it is ‘warehouse-sized’ in order to store his prodigious, unsellable output.

Having suffered from Hodgkin lymphoma in his late twenties, Feld attributes his unlikely friendship with a man thirty years his senior to the sense of rebirth they share. Guston has been reborn through sloughing off the constrains of abstraction while Feld — more literally — has re-emerged as a person without the threat of death hanging over him. He claims the experience of surviving cancer has narrowed and increased the perception of his vision, enabling him to see Guston’s paintings more intensely than any other artworks he’s encountered before or since. The singular interpretations Feld includes in Guston in Time bear out this claim.

Guston’s post-Marlborough paintings are littered with household objects such as shoes, lightbulbs, books, kettles and bottles. Guston never explained these recurring motifs and it was unclear to what extent he understood his own obsessions but for Feld it is obvious that this is not Duchampian irony being employed by Guston — ceci n’est pas une pipe. Instead, the household detritus represents a celebration of the ‘crap of life not for its own ironic sake but as the ever-present still life that surrounds the embarrassingly, even tragically human.’

Feld takes a similarly resolute view of Guston’s celebrated New York School period, arguing that his paintings from that time were, in fact, ‘forced’ to look abstract; an accusation Guston freely admits to in one of his letters to Feld — ‘I knew it at the time but couldn’t tell anyone.’ And it is in fact clear, when you closely examine paintings like Beggar’s Joys (1954-55) and Dial (1956) that there is some kind of underlying structure running through them in the way the paint is layered most heavily in the centre of the canvas. The forcedness of the abstraction becomes ever more obvious in later pictures such as Painter III (1963) and Head I (1965), where the unsettling suggestions of figures linger within the brush-strokes, like the shapes that appear through the static of a poor TV signal. Guston goes on to tell Feld in a subsequent letter that ‘all you say — every word, matches my own sensations… your thoughts are the only things that has happened to me this year of any import.’

On one of the few occasions they disagree, during a talk at Boston University, Feld bristles at Guston’s suggestion (‘So transpositional. So obvious.’) that his work is allegorical. With his ‘psychologically cataracted’ vision, Feld understands that the power of Guston’s late paintings — the sense they give off that there is something remarkable and unique about them — is derived from their resistance to easy interpretation. While he provides a clear snapshot of the last four years of his friend’s life in Guston in Time, Feld doesn’t succumb to the temptation to give anything other than deeply personal readings of Guston’s paintings, providing in the process a unique view of an deeply enigmatic artist’s work.

//

Patrick Christie Patrick Christie is a writer from London. His short stories, reviews and essays have appeared in The London Magazine, Litro Magazine, Review 31, Necessary Fiction, The Mechanics’ Institute Review and elsewhere. He holds an MFA in Creative Writing from Birkbeck, University of London. https://www.patrickchristie.co.uk/

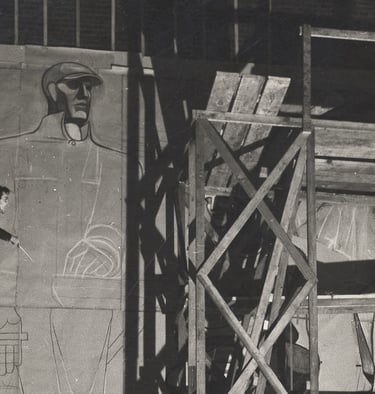

[image: from Guston sketching a mural for the N.Y. World's Fair, 1939]