Appropriations and Counter-Appropriations

Review of >> The Weather in Fritz Bemelmans Park by Holly Tavel

The Weather in Fritz Bemelmans Park, Holly Tavel, Equus Press, 2015.

Louis presented the book and I merely deployed my staring arm and stared at the cover. Have you read this one, asked Louis, because Holly Tavel has got, I think, a similar sense of humour to your own. Which reminded him, as he stood there before Louis and as he listened to Louis tell him this about Holly Tavel’s sense of humour and his own, about something someone had recently said concerning his latest novel, namely, that this someone else (actually, called Roy) found parts of it quite funny, and this surprised him, even though he had found parts of it quite funny to write.

In any case, none of this much mattered to the interaction in question, and the man before Louis took the book that Louis was offering him to have, and flew back with it, and did subsequently read it for the first time, the full, and complete list of short stories under its title The Weather in Fritz Bemelmans Park, and did this in late 2024 even though the book had been out in the world already for nigh on a decade. This should have been long enough for the author to have found the time to get the book and read it, given he had more than once claimed to be a follower, even an admirer, of the press that published it (the very fine Equus Press). But the author felt, on reflection, that he might have said quite a bit more to Louis than he actually did, and that he ought really to have said that he felt as though he already knew The Weather in Fritz Bemelmans Park quite well and that it came as no surprise to hear Louis say what he did.

Actually, he had himself thought things, passages even, that were similar, and in a sense, he felt plagiarised by Holly Tavel, and Louis should know that, because in many ways he anticipated this book, not only with his sense of humour (which surely existed in some form back in 2015), but in its topics and approaches too. And that he could already testify on those days when he felt good about his own writing that this book by Holly Tavel was actually rather magnificent, and that he agreed it might be nice to see another book by Holly Tavel, whose lines he felt like he already knew, especially the funny ones.

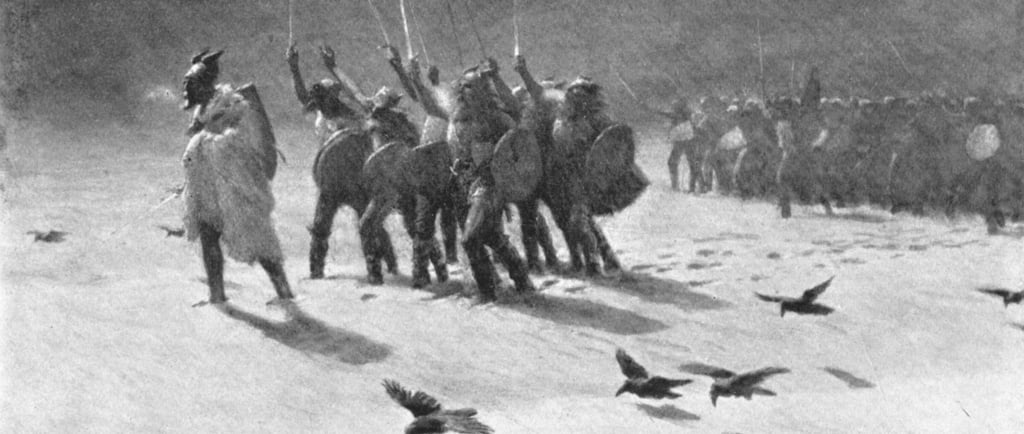

But then, there were many lines (most of them perhaps) that he could never have written, or had he written them, he would have deleted them (and so could still claim to have possibly written them) such as the line: ‘The horizon swung loose on its hinges, the sky unraveled like an old sweater, the ground beneath him cleared its dusty throat and coughed up a forest of steel girders’. Or the line: ‘Older Brother […] glad-handed his way through the Great Depression, all slow plaid and fresh prairie armpit’. He thought about this line, and the other one, and others too, not quite sure why he liked them. Or indeed, the opening passage of the short story in which each line appears, and which is called A Brief History of the Viking Conquest of America—

Big Ole walked across the sea from Norway to Newfoundland, said Father. He left behind him a fat wife with a face scorched and dull as an old copper pot, a herd of ramshackle goats, and a bevy of children who would not shut their pie-holes. Halfway across the sea he met Harald the Mad, who was headed back the other way with his bride atop his head. The bridal veil gathered bluefins in its mesh, and two virginial blonde braids skimmed the foamy swells. Two monoliths met in the middle of the sea, said Father. Do I even need to mention that their torsos were epic?

Or indeed—

By the time we arrived at the old trading post, carrying with us the rubble of a hundred villages, it was too late. The mighty fist of industry had come crashing down. The shantytowns lay on their backs, dead to the world. Washed in cool fluorescent luminance, a quincunx of shopping aisles splayed out from a central point an inch across, clad in fake terrazzo.

Which he admired (alongside many other such passages) for simultaneously conjuring up and ridiculing an entire nation over on one side of the Atlantic that surely does not deserve to exist, and, by association, another whole set of nations (not yet the Old World) on the other side that surely do not deserve to exist either.

He has long considered it good practice to imagine meeting the author of the book you are reviewing—a prompt to honesty and restraint, he supposed—and he had imagined meeting Holly Tavel who will have read his review, this review, in which he laid some kind of claim on her work (whilst also, earnestly, disavowing the rest of it), and he had already imagined himself apologising somewhat awkwardly, but justifying himself nonetheless by saying, doesn’t every author work to appropriate the work of another, and so, isn’t every author who knows about that simply trying to avoid their own appropriation, and really, isn’t this what writing is, he said, that is to say, acts of appropriation and counter-appropriation, and if he went a little too far, perhaps, by claiming she had actually plagiarised him by writing in a manner that he could identify with, the fault was certainly with Louis, not himself, for suggesting that his sense of humour was similar to hers (or hers to his, depending on your order of priority). This was surely enough reason to goad him into appropriating an author who had the temerity to begin publishing rather good (well, rather excellent) fiction, several years before he began publishing his.

//

Ansgar Allen is the author of books including a short history of Cynicism, and the novels, Black Vellum, Plague Theatre, The Wake and the Manuscript and The Sick List.

[image: A Viking Foray, John Charles Dollman, 1909]