Ansgar Allen’s Experimental Fiction as Meta-Critique

Notes on The Wake and the Manuscript (2022); Plague Theatre (2022); Midden Hill (2025); Jonathan Martin (2025)

The Wake and the Manuscript, Anti-Oedipus Press, 2022; Plague Theatre, Equus Press, 2022; Midden Hill, Schism 2, 2025; Jonathan Martin, Equus Press, 2025.

Ansgar Allen’s work has long interrogated institutional structures, especially those of education such as the archive, the classroom, or more broadly hierarchical assessment of any kind. This by enacting a pedagogy of failure: his writing foregrounds uncertainty, digression, fragmentation, and the impossibility of closure. In so doing, Allen liberates critique from the authority it often presumes, rewiring it as lived, embodied, and self‑questioning: a critique that teaches through collapse. This essay-cum-review shall consider Allen’s four recent works of fiction as a sustained meta-critiques of institutionalised education, esp. of the archive. In The Wake and the Manuscript, scholarship is exposed as recursive palimpsest; in Plague Theatre, institutions collapse into theatrical ruins; in Midden Hill, the mind exudes civilisational waste; and in Jonathan Martin, biography survives only through ruin and bricolage. Throughout, the archive is not a guarantor of continuity but a process of failure, residue, and disintegration.

1. Allen’s novel, The Wake and the Manuscript (2022), deploys fragmented narrative and theoretical reflection to question knowledge transmission, argumentation, and authority. While formally hybrid (part memoir, part philosophy), it serves as a metacritique of academic pedagogy, positioning the act of critical thinking itself as a performative failure of mastery. The Wake and the Manuscript confronts the ghostly persistence of texts not through linear commentary but via collage, reflection, erasure, and marginalia. It is as if the “manuscript” never finishes and the “wake” remains incomplete.

This allows Allen to stage a critique of educational fetishisation of linear argument and archival consolidation, and to venture the provocative suggestion that knowledge is always-already in ruin, always implicated in absence. In this book, the essay-form vacillates between first‑person recollection, speculative discourse, and detritus‑like footnotes. We are invited into an unstable epistemic space where testimony is incomplete and argument yields to reverie. The Wake and the Manuscript therefore models both the failure and the necessity of critique: a literary project in which critique becomes a form of ongoing incompletion:

Only after the experience of the body once directly felt in its uncontrollable excess has been diminished by the organising mechanisms of a basically ruthless educational imposition… only once the experience of the body has been lost… can its story be told and the meaning of its presence be rendered intelligible.[1]

This passage situates education as a form of archival violence: schooling erases the body's unmediated sensation, domesticating it and archiving the residue as something narratable. The very act of putting bodily experience into language is secondary, for it is archival, framed by institutional protocols that impose order. Allen exposes the archive as a site of loss and suppression, where meaning is manufactured only after experience is domesticated.

That the manuscript is an object to be guarded, stolen, iterated, destroyed, and recreated, is brought home in the following passage:

He kept it in a very definite place… somewhere hidden… I would have to employ all my ingenuity… to get their papers… Which was now the third complete iteration in existence—it would be the fourth if I had not destroyed the first stack. (51)

Each “version” becomes an archival copy, replete with the history of theft and erasure. The reader/speaker both mourns and enacts the destruction of knowledge, suggesting that institutional archives are repeat performances of theft under the guise of preservation. The gradient of versions evokes Derrida’s notion of the archive as repetition and violence. And this is not yet taking into account the finnicky character of the reader’s attention, constantly fracturing, flying off in various directions, straying from text into memory and fantasy:

For some sentences I had been picking words off the page and running them through my mind whilst thinking completely different thoughts. It is as if the reading bit of the brain separates from all other parts and just trundles on regardless. I find myself doing this often enough even when I am interested in what I am reading. I notice, lines, pages later, that I have not been attending to what I have been reading even though the words have been read and my eye gaze has been tracking across those words, along each line and then to the next. I realise, belatedly, that my mind has wandered, and I return, and tell myself to focus, unless what I have been reading has not struck me as worth re-reading, in which case I continue, glad of the pages I have missed, or I cease reading entirely. I had been thinking of the small misshapen trees on the island which did not yet have leaves when I saw them, and were in outline, angular, abused by wind, hardly living in fact. (81-2)

The archive here is porous, non-hierarchical: leafing through the manuscript triggers associative drift. The “misshapen trees” become an image of archiving degradation, an emblem for distorted cognition. Allen’s use of digression and associative slippage turns reading into an archival performance: document plus detritus, text plus organic ruin.

The Wake and the Manuscript portrays the archive in roughly three interrelated modes: as a suppressive institution, where education archives experience by erasing the body's immediate excess before permitting narrative; as a contested repository of artifact variants, where manuscripts get stolen, hidden, destroyed, repeatedly iterated, and where knowledge becomes transactional and volatile; and as an associative field, where reading is not linear but associative—attention is archival, drifting, resistant to institutional constraint. Allen’s The Wake and the Manuscript thus operates as a literary anti-archive, one that critiques how education and institutional memory discipline experience. It archives not to consolidate knowledge, but to expose the rupture between body, text, and identity—and to insist on the fragment as site of knowledge, the ruin as vocabulary of dissent.

2. In Plague Theatre (2022), Allen stages the societal and intellectual collapse of norms under conditions of disease, isolation, and socio-political upheaval. The book reads like a libretto or ensemble piece: voices fragment, actors cross roles, spectators become performers. The theatrical register serves to expose institutions—and especially educational performance—as spectacles built atop fragile certainties. The framing of course is Artaud’s “Theatre and the Plague” from Theatre and Its Double, treated not as source text but as contaminant: something that destabilises narrative, compels rewriting, and undermines the intellectual apparatus of interpretation. Artaud is not so much quoted or explained; he is absorbed and redeployed as a meta-critical device:

I was determined not to study Artaud, there is no studying Artaud as I knew well. Only fools set about studying Artaud. Writers like Artaud are destroyed by study. Writers such as Artaud make fools of those who write about them and have a way of turning all acolytes into idiots.[2]

Here, as elsewhere, Allen targets a concrete pedagogical practice (the scholarly master-narrative or historicising study of disruptive artists) and shows how that practice domesticates its object. The claim is programmatic: certain phenomena resist the analytic apparatus; the classroom’s ambition to “explain” can therefore be an act of epistemic violence. Allen’s theatricalisation of crisis does not preach but rather enacts collapse. Readers observe the dissolution of meaning-makers, of the certainties of method, of the seductions of hierarchisation.

In this sense, Plague Theatre dramatises a critique of educational stratagems that promise order through mastery, showing instead how knowledge circulates in the voided space between stage and audience when everything ordered unravels. Allen positions such institutional spaces as universities and museums as dead archives: sterile environments where living thought goes to die. In the words of his narrator, “[t]he intellectual persona is always a miserable creature and a fraud… museums are ‘destroyed by intellects’” (33-4). This furious dismissal of the intellectual subject attacks the very agent of formal pedagogy. Allen insists that the habit of pre-framing (questions, theories, conceptual schemas) pre-empts encounter and deadens what might be known; pedagogy’s speaking-position becomes a self-annihilating filter that prevents the material’s vitality from reaching us.

The intellect becomes archival in its own right, a corpse aestheticising itself. This archiving through institutionalisation is precisely what Allen’s fiction destabilises. Plague Theatre stages the archive’s collapse under its own weight, with plague conceived as historical meta-archive: not a contained event, but a systemic disruption that propagates its own textual field. Histories of plague become theatrical scripts of decomposition, breaking narratives, exploding chronology, and rendering documentation itself suspect.

There are several passages in Plague Theatre beyond the Artaud framing that illustrate Ansgar Allen’s method of experimental fiction as meta-critique, especially in relation to pedagogy, knowledge, and institutionalised habit. On functional contentment and the futility of education as a corrective, Allen’s narrator has this to impart:

As such, it cannot be combatted by knowledge or understanding or training or conscience or education. We may express dissatisfaction with our era or elements of it, but we are, in functional terms, still satisfied enough to use its products and eat its foodstuffs, to live in its world and inhabit its architectures. (99)

This undermines any faith in pedagogy as a reformative practice; knowledge itself becomes complicit in sustaining destructive conditions. Moreover, everyday institutionalised habit has a way of producing a certain type of blindness that is structurally maintained by routine, from which pedagogy cannot awaken us:

These engineers still do not know themselves, they have not confronted themselves, not because they are blind or deluded or callous or indifferent, but because they are alive at a time that produces blindness as a function of everyday habit, the need to fill up the car, put out the bin, pay the toll. The destruction of habit will be the end of their world and the continuation of another less destructive way of life. (108)

Not only blinding, inherited systems of belief and habits are also shown in Plague Theatre to be inescapable where mere acts of will are concerned:

I understood by my own attempts, and my own failures, that habits cannot be escaped by an act of will, and that others will suffer as my aunt and mother suffered when I attempted to break with the systems of belief and everyday sense they lived by. (109)

This pushes Allen’s fiction into the realm of lived pedagogy: education, here, is a failed attempt to reconfigure inherited structures of habit and sense. Beyond its Artaudian preface, Plague Theatre engages in an experimental critique of the limits of education, pedagogy, and institutional knowledge, insisting that knowledge itself is always already folded into the very structures of destruction it might claim to resist. Allen’s core claim about pedagogy and institutions here is that institutional modes of knowledge (museums, archives, scholarly study) tend to ossify, domesticate, or annihilate what they seek to render legible. The book therefore stages a tension between that deadening apparatus and forms of experience (plague / theatre / writing / performance) that resist capture – a central dimension of Allen’s critique of institutional epistemology.

3. Allen’s latest publication, Midden Hill (2025) continues his project of experimental fiction as meta-critique, advancing a meditation on the limits of knowledge, the architectures of pedagogy, and the bodily costs of intellectual labour. Unlike straightforward allegory or conventional philosophical treatise, Midden Hill inhabits the zone between narrative, parable, and fragmentary essay. The text stages the experience of thinking as an ordeal: not a progressive journey towards enlightenment but a continual brushing up against obscurity, exhaustion, and the violent enclosures of institutional knowledge. Allen’s narrative centres on an island composed entirely of civilisation’s waste: cultural artifacts, detritus, language fragments, archival trash. Visitors to the island report distorted speech and perception, as if society’s detritus infects cognition. One visitor barely survives and narrates from the margin.

Allen’s midden hill becomes, again, a site of pedagogy: instead of masterful knowledge, one confronts sedimented traces of meaning made and unmade. The text challenges the erasure endemic to institutional education, which suppresses debris deemed irrelevant, ephemeral, and non‑canonical. On Midden Hill, everything counts, yet nothing stands intact. This invert‑pedagogy transforms failure, rupture, and contamination into the basis for new understanding:

Think of the mind as a vessel that takes in its exterior. It must surely liquify what it incorporates, boil it down, and then extrude only the finest scum of that concoction, otherwise the vessel would fill with a few short glances at the world it sees. […] We may think of speech as a mechanism of removal, of the mouth as the first orifice of expulsion, and of the necessity of talking as the necessity of making room in the mind for its growth within the confines of the head. The skull cavity is the ultimate limit that halts growth and maintains humanity in its comparative ignorance.[3]

Here, Allen rewrites classical metaphors of knowledge as nourishment (Plato’s dietetics of the soul, Bacon’s digestion of experience) into grotesque corporeal parody. In so doing he provides an arch-archival metaphor: the mind consumes and digests exterior chaos, but only extrudes intellectual sediment. The archive, in this sense, is the residue of civilisation’s failure, a midden of memory and ruin. The island in Midden Hill becomes physical rhyme to that mental midden: both archives and archives failing, sediment washed into the world.

A second recurring image is that of the weed as figure for knowledge’s unstable borders:

There is no line […], but merely a roughly defined rim, a diminishment marked by the fringes of the weed. Likewise, there is no absolute line where the frontiers of knowledge pass over to their own darkness. As the weed showed by encapsulating both […], the border of each is indeterminate. (44)

Here, epistemology is not a matter of sharp frontiers but of indistinct fringes, proliferating like weeds. Pedagogy’s desire for demarcation is continually undermined by the indeterminate nature of perception and the encroachment of unknowing. The critique of pedagogy extends into the most minutious of details, like a depiction of the house of the overseer:

When you clawed your fingers under the front door of the house to open it, he said to me, you submitted yourself to the logic of this place, to the design of the house. […] The only way we can leave is by separating our perception from the perception of our surroundings, my employer said. (114-5)

The architecture of the appositely-titled overseer’s house doubles as the architecture of education: to enter is to accept its logic, to have one’s perception formed in advance. Liberation requires nothing less than a rupture between perception and world, a radical act of unlearning that severs the tie to institutional surroundings. Allen makes his perhaps most provocative move when theorising wakefulness as a killing state:

The condition of existence for the mind, its wakefulness, is also the killing state of the mind. The mind deteriorates when it is awake, and if it remains awake too long, the killing state takes over. […] To work as a doctor is to spend more time than would be naturally spent in a killing state of mind. (69-70)

Here the act of thinking itself is shown to corrode. Pedagogical labour, whether in medicine or philosophy, becomes indistinguishable from an exposure to death. The doctor or teacher, required to remain awake beyond natural thresholds, inhabits a state that destroys the very faculties sought to develop.

Across these metaphors, Midden Hill dramatises the paradox of education: that knowledge both sustains and kills, liberates and entraps. Allen’s prose refuses the consolations of philosophical clarity, but instead makes palpable the exhaustion, violence, and futility at the heart of the pedagogical project, positioning fiction itself as the only form capable of enacting this critique from within.

4. In his new novel Jonathan Martin, forthcoming with Equus in November, Allen writes biography as “anarchive”, resurrecting the incendiary life of the 19th-century outsider who set fire to York Minster in 1829. Martin’s life — at once prophetic, deranged, and tragically emblematic of his age — becomes the ground for Allen’s boldest experiment in historical fiction to date. Blending archival fragments, self-published pamphlets, trial records, and fictionalised reconstructions, Jonathan Martin asks: was Martin a prophet or a lunatic, an arsonist or a visionary?

Jonathan Martin (2025) fictionalises a historical persona through an illustrated, fragmentary hybrid of biography, memoir, and visual collage. Allen’s mode here—tentatively reported—suggests that Martin’s story is told through archival rubble, multiple versions, illustrative layers, and retrenchments that expose the instability of identity, truth, and the educational project of history writing. If The Wake and the Manuscript destabilises text, Plague Theatre destabilises social performance, and Midden Hill destabilises the binary of information and noise, Jonathan Martin destabilises biographical authority, positioning identity as a site of contested narratives rather than coherent truth. This aligns with Allen’s broader critique: identity is not taught but edited, overwritten, discarded, rather than discovered.

The protagonist, Jonathan Martin, is confined in Bedlam, and the biography reconstructs his escapes, prophetic vandalism, asylum art created from tools repurposed into symbolic objects like a carved giant (colossus) announcing destruction. The text reconstructs Martin’s life through the fragments of his own iconoclastic performances, asylum notes, and mad prophecies. It enacts “biography as anarchive”: a reconstruction assembled from rebel scraps, not institutionalised records. Identity is unmade and remade via such remnants as Benjamin Franklin’s dream-logic, carved furniture, condemned inmates turned psyche‑mythos. Narrative coherence is suspended; biography is embedded in ruin.

Martin embodies both the figure of the religious visionary and the social outcast, a man suspended between inspiration and confinement, between prophetic speech and medical diagnosis. His texts, letters, and trial testimonies read less as straightforward autobiography than as experimental fragments: part denunciation, part hallucination, part legal defence, part millenarian sermon. The blurry distinction between priest, prophet, and lunatic emerges as one of the book’s central themes:

The priest is confined to the work of commentary, where all miracles and all revelations are essentially sealed off and put out of reach, having occurred so long ago that they are at once ancient and outside of history. The lunatic and the prophet act on the contrary impulse and defy the sclerotic effect of tradition on thought […]. The most difficult message for the prophet is to announce the end of things, that everything is fallen, and nothing can be done.[4]

Here Martin’s language, whether his own or refracted through reportage, insists on the necessity of a barbaric, disruptive speech—speech that refuses to become commentary, and instead declares collapse. This prophetic posture is inseparable from Martin’s self-understanding at trial, where the state attempts to reduce his visions to the medical category of monomania:

Jonathan was declared insane at his trial and so allowed to live because he was a lunatic and not a prophet. He never forgave Richard the Quartermaster-Sergeant for arranging this diagnosis as his defence. As a lunatic, he could be excused. As a prophet, he would have been executed […]. There is a long tradition of identifying and executing false prophets. There is no similar tradition for false lunatics. (41–2)

The legal system thus weaponises medical discourse in order to neutralise the radical threat of prophecy. To be mad is survivable; to be a prophet is unforgivable. Martin’s letters and sermons—nailed to the doors of York churches—reveal the uncompromising violence of his biblical rhetoric:

—Oh you Fools and Gready wolves your time is short and the Judgement of God is Hanging over your Giltey Heades—your torments will be ten thousent Fauld mor you Deserves […] God is about to cum out of his place to take vangins on you, and all those that obay your Blind Halish Doctren, for it Cums from the black reagens of the Damd. (163)

The orthographic roughness, the urgency of repetition, and the raw spelling intensify the sense of unfiltered prophecy. Language here is not polished but eruptive, its very errors part of its visionary force. Finally, Martin’s refusal of guilt illuminates the paradox of prophetic violence:

When it was announced at court that Jonathan Martin stood accused of having unlawfully, maliciously, and wilfully set fire to the Cathedral Church of York, the accused objected only to the word maliciously—not maliciously, he shouted out. (170)

For Martin, destruction is not malicious but necessary, even righteous: a gesture against the “edifice” rather than the individuals who serve it. Across these fragments, Martin emerges as a writer whose prophetic speech collapses into lunacy, whose fire is both literal and allegorical, whose texts dissolve the line between witness, heretic, and visionary. Like in Midden Hill, Allen here turns madness into critique, exposing how institutions of church, law, and medicine conspire to contain unruly forms of knowledge.

Allen’s prose, at turns Joycean, Woolfian, and Beckettian, inhabits Martin’s fractured language and his millenarian visions, bringing to life a world teetering between religious ecstasy, madness, and political upheaval. Why invoke these three modernists? Allen’s prose channels Jonathan Martin’s broken orthographies and idiosyncratic pamphlets, revelling in distorted spellings, shifting registers, and polyphonic layering of voices, in a mode reminiscent of Joyce’s writings. Its Joycean dimension foregrounds language as material that is playful, excessive, unstable. At the same time, Allen often slows into a more fluid, stream-of-consciousness mode that recalls Woolf’s explorations of inner life, the prose’s rhythms of perception, memory, and dream capturing how Martin’s consciousness drifts between past and present, vision and paranoia. Finally, in its sparer, darker passages, Allen’s prose bears the stamp of Beckett. Fragmentary sentences, bleak humour, repetition, and a sense of language exhausted by its own limits produce a Beckettian minimalism. This tone surfaces especially in depictions of Martin’s confinement and decline, where prose strips itself bare, circling around silence and futility.

A powerful meditation on authorial voice, writing as prophecy, and the boundaries between sanity and inspiration, Jonathan Martin continues Allen’s exploration of institutional education and deviance from social order. It is a work of fiction that refuses to perpetuate the illusion of coherence, confronting the reader instead with the broken totality of a life lived on the edge of destruction.

5. Across these four rich texts, Allen’s writing engages in an evolving meditation on the nature of the archive: what it preserves, what it erases, and how it corrodes what it contains. Each work is less a novel in the conventional sense than anti-archival praxis, turning received forms of scholasticism, institution, biography, and memory into sites of disintegration.

The Wake and the Manuscript stages a confrontation with the archive of scholarship itself. It presents scholastic fragments and recursive exegesis as a kind of endless palimpsest, where manuscripts are not so much vessels of preservation as occasions for perpetual rewriting. Its form mimics commentary—footnotes, scholia, textual glosses—but divests these of stabilising authority. The result is an archive incapable of closing upon itself: each fragment demands another, each gloss multiplies further questions. Critique, here, is not synthesis but recursion, writing folded back on itself in interminable “wakefulness” of handwriting.

From there, Plague Theatre reorients the archive around institutional collapse. Framed by an engagement with Artaud’s theory and practice of the theatre, the book treats the manuscript as contagion: a text that wreaks disorder by undoing the very value-systems it inhabits. In this work, institutions—legal, medical, as much as theatrical—are no mere repositories of knowledge but theatres of ruin. The archive becomes a stage on which collapse is dramatised; knowledge is shown not as accumulation but as pathology, an anxiety-ridden performance undermining itself.

Midden Hill internalises the archive, turning from external institutions to the mind–body interface. Here, civilisation’s refuse is processed through the metaphor of the skull as vessel: the mind takes in, liquefies, and extrudes the detritus of experience. The archive is figured as an expulsion machine, producing scum, residue, and waste rather than knowledge. Pedagogy is mutilation, philosophy born of trepanning. What this brings about is a deeply somatic epistemology: the archive becomes not a library but a midden-heap, where consciousness itself is the site of civilisational debris.

Finally, Allen’s reconstruction of Jonathan Martin extends this anti-archival poetics to biography. Martin’s life is presented through ruin and bricolage: trial transcripts, sermons, denunciations nailed to church doors, diagnoses of lunacy. His identity is archived only through fragments of wreckage, preserved in the interstices between legal categories (prophet or lunatic), institutional containment (asylum), and iconoclastic violence (fire). Here the archive is explicitly political: a life that might have been extinguished in execution instead survives as textual debris, assembled from fragments that institutions sought either to pathologise or destroy.

Ansgar Allen’s literary-philosophical project enriches contemporary thinking by demonstrating that critique need not command clarity to be instructive. His texts sidestep the expectation that philosophical discourse be coherent, linear, or authoritative. Instead, they teach through artful disintegration, ambiguous gestures, and the construction of ruin. As both theorist and writer, Allen offers a pedagogy of the fragment, a critique that educates by refusing the confidence of normative knowledge. His fiction refuses coherence so that the archive remains process rather than product, critique rather than preservation, prompting us to ask not how to arrive, but how to inhabit what never arrives: epistemic residue, theatrical collapse, civilisational midden, biographical archive. In doing so, Allen positions experimental fiction itself as an act of education: not through transmission, but through the experience of collapse as re-formation.

[1] Ansgar Allen, The Wake and the Manuscript (Anti-Oedipus Press, 2022) 26. All in-text references are to this edition.

[2] Ansgar Allen, Plague Theatre (Equus Press, 2022) 25. All in-text references are to this edition.

[3] Ansgar Allen, Midden Hill (Schism2, 2025) 129. All in-text references are to this edition.

[4] Ansgar Allen, Jonathan Martin (forthcoming with Equus Press, 2025) 39–40. All in-text references are to this edition.

//

David Vichnar teaches at Charles University Prague. He is also active as an editor, publisher and translator. His translations from/into English include important works of the French, German and Anglophone avantgardes. He directs Prague Microfestival and manages Litteraria Pragensia Books and Equus Press. His articles on contemporary experimental writers as well as translations of contemporary poetry and fiction—Czech, German, French and Anglophone—have appeared in numerous journals and magazines.

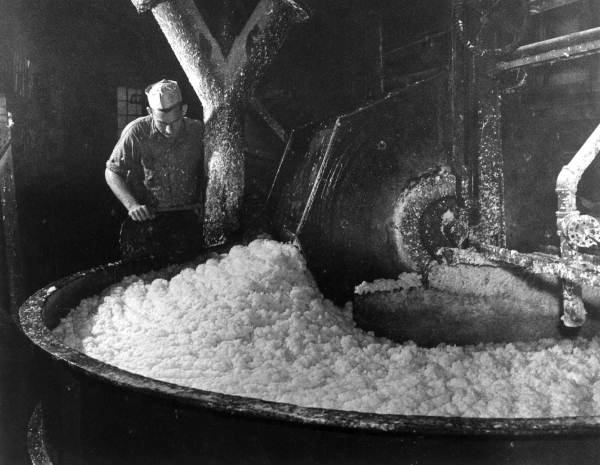

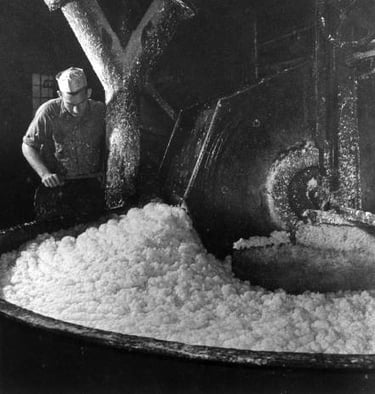

[image: A worker mixing pulp at a paper mill near Pensacola, 1947]